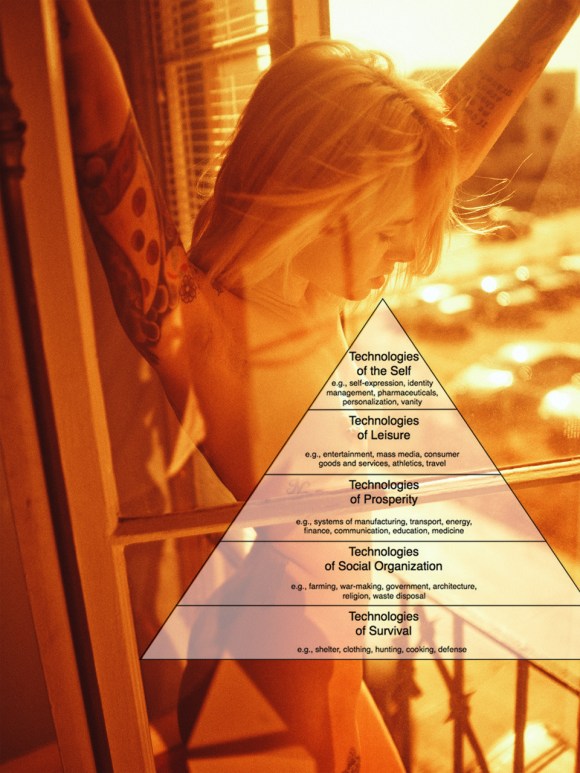

…there’s a Hierarchy of Innovation that runs in parallel with Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs.

Maslow argued that human needs progress through five stages, with each new stage requiring the fulfillment of lower-level, or more basic, needs. So first we need to meet our most primitive Physiological needs, and that frees us to focus on our needs for Safety, and once our needs for Safety are met, we can attend to our needs for Belongingness, and then on to our needs for personal Esteem, and finally to our needs for Self-Actualization.

If you look at Maslow’s hierarchy as an inflexible structure, with clear boundaries between its levels, it falls apart. Our needs are messy, and the boundaries between them are porous. A caveman probably pursued self-esteem and self-actualization, to some degree, just as we today spend effort seeking to fulfill our physical needs. But if you look at the hierarchy as a map of human focus, or of emphasis, then it makes sense – and indeed seems to be born out by history. In short: The more comfortable you are, the more time you spend thinking about yourself.

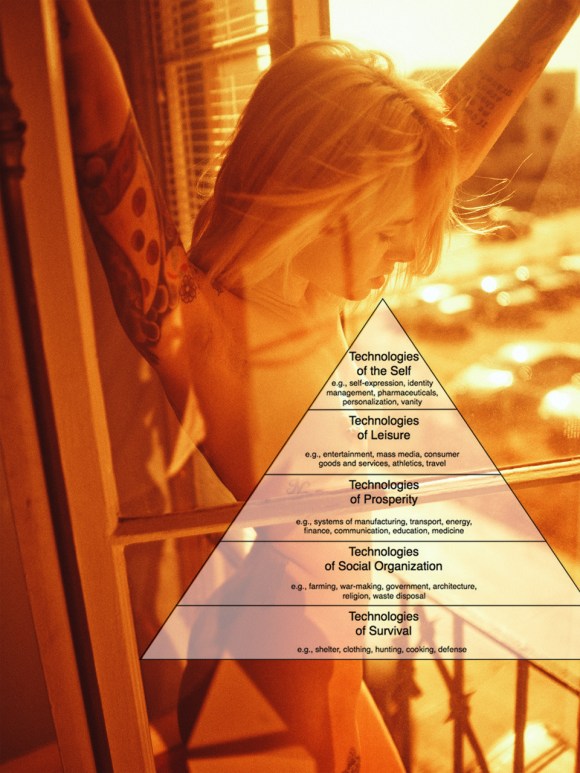

If progress is shaped by human needs, then general shifts in needs would also bring shifts in the nature of technological innovation. The tools we invent would move through the hierarchy of needs, from tools that help safeguard our bodies on up to tools that allow us to modify our internal states, from tools of survival to tools of the self.

The focus, or emphasis, of innovation moves up through five stages, propelled by shifts in the needs we seek to fulfill. In the beginning come Technologies of Survival (think fire), then Technologies of Social Organization (think cathedral), then Technologies of Prosperity (think steam engine), then technologies of leisure (think TV), and finally Technologies of the Self (think Facebook, or Prozac).

As with Maslow’s hierarchy, you shouldn’t look at my hierarchy as a rigid one. Innovation today continues at all five levels. But the rewards, both monetary and reputational, are greatest at the highest level (Technologies of the Self), which has the effect of shunting investment, attention, and activity in that direction. We’re already physically comfortable, so getting a little more physically comfortable doesn’t seem particularly pressing. We’ve become inward looking, and what we crave are more powerful tools for modifying our internal state or projecting that state outward. An entrepreneur has a greater prospect of fame and riches if he creates, say, a popular social-networking tool than if he creates a faster, more efficient system for mass transit. The arc of innovation, to put a dark spin on it, is toward decadence.

One of the consequences is that, as we move to the top level of the innovation hierarchy, the inventions have less visible, less transformative effects. We’re no longer changing the shape of the physical world or even of society, as it manifests itself in the physical world. We’re altering internal states, transforming the invisible self. Not surprisingly, when you step back and take a broad view, it looks like stagnation – it looks like nothing is changing very much. That’s particularly true when you compare what’s happening today with what happened a hundred years ago, when our focus on Technologies of Prosperity was peaking and our focus on Technologies of Leisure was also rapidly increasing, bringing a highly visible transformation of our physical circumstances.

http://www.roughtype.com/?p=1603

/image: Kesler Tran http://bit.ly/1f23A2K

// Weighing, and balancing this, against the PR wave spotlighting the reported *decrease* of creativity scores in the U.S., while other countries emphasize and prioritize creativity development. “The Creativity Crisis” http://www.newsweek.com/creativity-crisis-74665 //