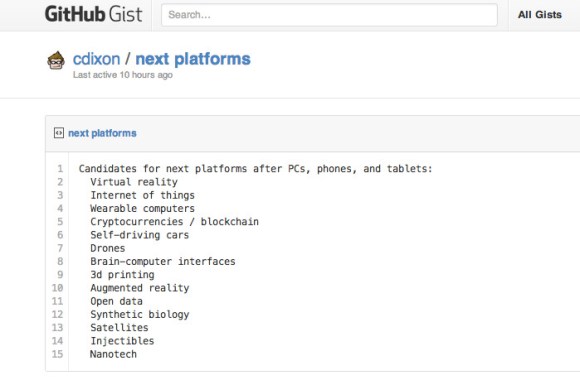

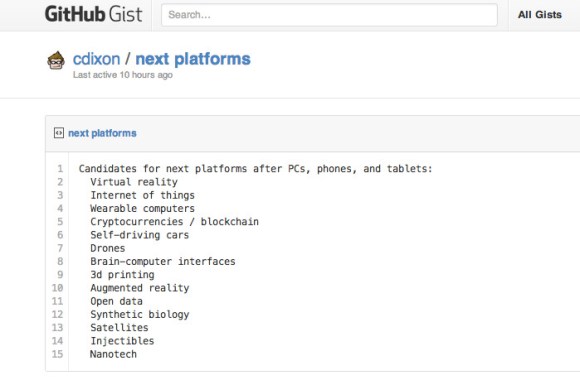

A Gist for: Candidates for next platforms after PC’s, phones and tablets.

I didn’t save it, but Outlier is using subReddits to announce new stock.

Platform mutations are cool!

A Gist for: Candidates for next platforms after PC’s, phones and tablets.

I didn’t save it, but Outlier is using subReddits to announce new stock.

Platform mutations are cool!

When technology companies look at goods that are built from the outside in, they generally see irrationality and inefficiency, a broken market just waiting to be corrected and “disrupted.” They believe that they can engineer so much value into these items that people will be swayed to buy goods built from the inside out, that the promise that drives hardware and software—“adopt this and benefit from its utility”—will convince people to upend their sartorial habits.

This is how you get products like Google Glass, which assumes that consumers prize utility so much that they’re willing to look like they have no interest whatsoever in having intimate relations with another human being.

I’m kind of joking about that, but I’m kind of not joking too.

The things that we wear aren’t just an expression of who we are, they are an expression of who we want to be with—as friends, as neighbors, as fans, as lovers. A shirt, a pair of glasses, a necktie, a pair of shoes…these are methods that we use to make a connection between our inner selves and other people. We use fashion to signal our particular humanity to other human beings. Fashion can be trite and superficial and, in my experience meeting members of the industry, it can be a magnet for some of the least interesting human beings on earth. Nevertheless it satisfies a deep-seated need for connectedness, and it’s an indispensable part of living in society.

Part of that indispensability, at least in consumer culture, is fashion’s endless variability, even within the dress codes that align us together into tribes. We could all choose to wear the same thing, and yet we don’t, even within groups who feel very much the same way about the same things. We need what we wear to both signal our belonging and highlight our apartness, to emphasize our individuality. And we find it intolerable when it promises to do that and fails, when someone else shows up in that same cocktail dress at that party that we’ve been waiting all season for.

http://qz.com/226927/google-android-io-are-not-the-wearables-weve-been-waiting-for/#/h/81036,1/

What, exactly, is mindfulness? How do you define it?

Langer: Mindfulness is the process of actively noticing new things. When you do that, it puts you in the present. It makes you more sensitive to context and perspective. It’s the essence of engagement. And it’s energy-begetting, not energy-consuming. The mistake most people make is to assume it’s stressful and exhausting—all this thinking. But what’s stressful is all the mindless negative evaluations we make and the worry that we’ll find problems and not be able to solve them.

We all seek stability. We want to hold things still, thinking that if we do, we can control them. But since everything is always changing, that doesn’t work. Actually, it causes you to lose control.

Take work processes. When people say, “This is the way to do it,” that’s not true. There are always many ways, and the way you choose should depend on the current context. You can’t solve today’s problems with yesterday’s solutions. So when someone says, “Learn this so it’s second nature,” let a bell go off in your head, because that means mindlessness. The rules you were given were the rules that worked for the person who created them, and the more different you are from that person, the worse they’re going to work for you. When you’re mindful, rules, routines, and goals guide you; they don’t govern you.

What are some of the specific benefits of being more mindful, according to your research?

Better performance, for one. We did a study with symphony musicians, who, it turns out, are bored to death. They’re playing the same pieces over and over again, and yet it’s a high-status job that they can’t easily walk away from. So we had groups of them perform. Some were told to replicate a previous performance they’d liked—that is, to play pretty mindlessly. Others were told to make their individual performance new in subtle ways—to play mindfully. Remember: This wasn’t jazz, so the changes were very subtle indeed. But when we played recordings of the symphonies for people who knew nothing about the study, they overwhelmingly preferred the mindfully played pieces. So here we had a group performance where everybody was doing their own thing, and it was better. There’s this view that if you let everyone do their own thing, chaos will reign. When people are doing their own thing in a rebellious way, yes, it might. But if everyone is working in the same context and is fully present, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t get a superior coordinated performance.

There are many other advantages to mindfulness. It’s easier to pay attention. You remember more of what you’ve done. You’re more creative. You’re able to take advantage of opportunities when they present themselves. You avert the danger not yet arisen. You like people better, and people like you better, because you’re less evaluative. You’re more charismatic.

The idea of procrastination and regret can go away, because if you know why you’re doing something, you don’t take yourself to task for not doing something else. If you’re fully present when you decide to prioritize this task or work at this firm or create this product or pursue this strategy, why would you regret it?

I’ve been studying this for nearly 40 years, and for almost any measure, we find that mindfulness generates a more positive result. That makes sense when you realize it’s a superordinate variable. No matter what you’re doing—eating a sandwich, doing an interview, working on some gizmo, writing a report—you’re doing it mindfully or mindlessly. When it’s the former, it leaves an imprint on what you do. At the very highest levels of any field—Fortune 50 CEOs, the most impressive artists and musicians, the top athletes, the best teachers and mechanics—you’ll find mindful people, because that’s the only way to get there.

http://hbr.org/2014/03/mindfulness-in-the-age-of-complexity/ar/1

Design is about intent.

Intent means purpose; something highly designed was crafted with intention in every creative decision.

Frank Lloyd Wright explained that intent drives design with the credo “form follows function“; P&G calls this being “purpose-built.” The designer is the person who answers the question “How should it be?”

Overarching intent is easy. The hard part is driving that conscious decision-making throughout every little choice in the creative process. Good designers have a clear sense of the overall purpose of their creation; great designers can say, “This is why we made that decision” about a thousand details.

The opposite of design, then, is the failure to develop and employ intent in making creative decisions.

—

This doesn’t sound hard, but, astonishingly, no other leading tech company makes intentional design choices like Apple. Instead, they all commit at least one of what I term the Three Design Evasions:

The first evasion: Preserving

The easiest way to avoid a decision is to not ask the question in the first place. Anyone who’s ever led a business project knows the temptation of recycling precedent – why reinvent the wheel?

But great designers know that sacred cows must always be evaluated for slaughter.

“Sentimentality doesn’t make for good design.”

—

The second evasion: Copying

Copying others’ design choices is the most obvious way to abdicate forming your own intent and having to make decisions yourself.

—

The third evasion: Delegating

Delegating is by far the most subtle, pernicious, and widespread of the three evasions, particularly among tech companies. Under the guise of being “user-driven” or providing “choice,” delegators leave crucial design decisions up to the user. One can even subdivide this tactic into three distinct flavors:

A) Offering a wide range of product choice

Many of the most successful hardware companies seem incapable of deciding how their products should be, so instead they offer variety:

Take Samsung again, which offers over a hundred distinct smartphones and tablets; this “spray and pray” strategy is the norm, not the exception, in mobile devices.

Google is taking this a step further, developing a modular smartphone that would “allow” consumers to separately purchase and swap components in and out.

Of course, PC makers like Lenovo, HP, and Dell have long epitomized choice, each offering a bewildering array of configurations.

On the software side, Microsoft couldn’t choose whether to prioritize legacy functionality or mobile optimization, so it offers both Windows 8 in “Pro” tablets or the more limited Windows RT.

The banner of “choice” is always good PR, and may even be good product strategy for many companies. But it’s not design. Design means curating the choice for the consumer. John Gruber summarizes Apple’s starkly limited product line well:

“Apple offers far fewer configurations. Thus, [Apple products] are, to most minds, subjectively better-designed – but objectively, they’re more designed. Apple makes more of the choices than do PC makers.”

As an analogy, giving someone birthday money instead of taking the time to choose a gift seems eminently logical – why limit the recipient’s choices? But the gifts we remember most fondly are seldom checks.

B) Trying to offer an omni-functional product

Good designers create things with specific uses in mind, which implies making purposeful trade-offs. Another way to abdicate design is refusing to accept those trade-offs; it feels better to make something that could be anything for anyone. Seth Godin calls this a design copout – creating something that “helps the user do whatever the user wants to do,” instead of expressing the creator’s intent.

Once more, Samsung is a prime example; David Pogue summed up his review of the Galaxy S5 thus:

“… if you had to characterize the direction Samsung has chosen for its new flagship phone – well, you couldn’t. There isn’t one … Overall, the sense you get of the S5 is that it was a dish prepared by a thousand cooks. It’s so crammed with features and options and palettes that it nearly sinks under its own weight.”

This unwillingness to choose, to say no – to exert intent – is also exactly what plagued Microsoft’s Surface, its “no compromises” hybrid tablet/laptop. Unsurprisingly, this jack-of-all-trades device is still a master of none.

Does this mean good design is assertive, ultimately subjective, even restrictive? Absolutely. As Marco Arment put it,

“Apple’s products are opinionated. They say, ‘We know what’s best for you. Here it is. Oh, that thing you want to do? We won’t let you do that because it would suck.’”

C) Deciding based on user testing

The final flavor of Delegating is a favorite of Internet software and services companies: using A/B testing (or some variant) to see which designs elicit the best metrics from users. Witness the descriptions of how design decisions get made at leading firms:

Google: “We think of design as a science. It doesn’t matter who is the favorite or how much you like this aesthetic versus that aesthetic. It all comes down to data. Run a 1% test [on 1% of the audience] and whichever design does best against the user-happiness metrics over a two-week period is the one we launch.”

Amazon: “We’ve always operated in a way where we let the data drive what to put in front of customers … We don’t have tastemakers deciding what our customers should read, listen to, and watch.”

Facebook: “It doesn’t matter what any individual person thinks about something new. Everything must be tested. It’s feature echolocation: we throw out an idea, and when the data comes back we look at the numbers. Whatever goes up, that’s what we do. We are slaves to the numbers. We don’t operate around innovation. We only optimize. We do what goes up.”

This kind of user testing – often dressed up as “failing fast” or “experimenting” – can be useful, but it’s not design. You can safely bet that Apple has never tested 41 shades of blue on users to decide the right color for its website links.

http://rampantinnovation.com/2014/05/13/design-is-about-intent/

Your choice of first customers is one of the most underappreciated, important decisions in the early life of a startup. It’s a one-way door, and one-way doors are expensive (it can be excruciating to turn back the clock once you start serving customers).

…

One way to think of it: your first customers are your first hires as marketers. You want them to be as good at their job as possible.

Imagine all your customers as you did before (in terms of how valuable they’ll find you, and how easy they’ll be to attract). Then, consider that some of them have influence on others. You’ll find pockets where one kind of customer influences another, and some customer classes who are widely influential, or influential to several important adjacent customer classes.

Think of this as a gradient of influence among your customers.

You want to target a class of customers, at first, who are as high up on that gradient as possible — even if they’re harder to attract (as I imagine security agencies were for Palantir) or you make less money from them (as OUYA did from its Kickstarter backers, where it priced the product as low as possible before knowing the cost to serve each customer).

Often, the type of customer who will ultimately pay your bills is not the best first customer, and that’s counterintuitive.

Notice I’m describing customer classes vs. individual customers. Many startups overweight the value of that one Fortune 50 logo, vs. the value of being known for serving one class of customers well. Better to dominate some initial market and then expand, than to have dispersed pockets of usage where each customer is famous.

There are many ways to slice the universe of potential customers into classes:

Industry — “tech companies”

Function — Bloomberg got its start focusing on bond traders

Reputation — “Top 100 best places to work companies”

Community or event — Foursquare sparked a fire at SXSW

—

Think about it like this: what’s the class of customers most admired by the entire universe of customers you might have? Define that admired class as narrowly as possible, to make it easier to find and serve them, and to get critical mass in at least one market.

http://also.roybahat.com/post/84933343626/picking-your-first-customers-the-gradient-of-influence

The most valuable compensation for working at a startup as opposed to a “normal job” is a dramatically higher rate-of-learning (ROL).

Your rate-of-learning is a better proxy for how successful you will be than your current salary or stock compensation because it’s a leading rather than lagging indicator.

Abandoning the cubicle at your normal job to throw yourself head-first into a startup is a fiery accelerant for growth, changing your career trajectory by orders of magnitude through a substantially increased rate-of-learning. To explain why, let’s define ROL:

Definition: Rate-of-learning is the velocity at which you are aggregating new insights and deploying them in ways that build value.

In physics, velocity is measured along two vectors: speed and magnitude. In this case, the pace at which you are uncovering new insights (speed) has a direct relationship with the leverage you accumulate deploying these new insights (magnitude). Whether this process of aggregating and deploying insights is in the form of writing code or driving growth, scaling this steep learning curve is the forging process that turns you into a badass full-stack developer or full-stack marketer with a high market value—not getting paid a large salary to sit in meetings all day.

There are three reasons why I believe rate-of-learning is your most valuable personal asset class:

Compounding interest on learning.

You may have noticed in the graph above that the line representing startup rate-of-learning is exponential while that of a normal job is linear. While this is more conceptual than anything else, it illustrates an important point: if you reach a fast enough rate-0f-learning you start generating compounding interest on those learnings.

Let’s use a real life example. Imagine you’re a growth marketer at a startup and uncover a new way to drive sign-ups by aggressively retargeting people who have visited your blog organically. You deploy the retargeting campaign and it works, so next, you find a way to generate more quality blog content by syndicating posts from experts in your space so you can attract even more eyeballs. Having successfully widened the top of your funnel, you switch gears and figure out how to dramatically increase conversion by personalizing sign-up page copy and background images based upon location data you’re pulling off a visitor’s IP address. This leads to another insight about a series of fields that can be moved out of the sign-up form and into the onboarding flow to reduce friction. The cumulative effect? You increase sign-ups by 20%.

In a startup, this series of experiments can happen over the course of a few days. In the alternative universe of a normal company you might be waiting a week for a small retargeting budget or approval from your manager. Therefore the valuable insights that should theoretically follow your initial insight may never come. If you extend this slower rate-of-learning over months or years, the opportunity cost of missed insights is massive.

Learning equals leverage.

People think having “f*** you” money is leverage, but in reality, a high rate-of-learning gives you more leverage than money does. If I were to give you a choice between wiring $10,000 to your checking account or an opportunity to uncover 50 powerful insights that could land you an awesome job at Airbnb or Dropbox, which would you take?

Another way to think about rate-of-learning dividends: the present value of money is low, especially when interest rates are at 0%, because you can’t generate as much compounding interest on money as you can on your learnings. So if you have a choice between getting paid $50K at a startup or $100K at a dying company, your future self will thank you for taking half the pay in exchange for a 3-5X ROL. A high rate-of-learning is the most bankable asset you can have in the startup world because it’s the vehicle by which longterm value is created, both within yourself and for your startup.

Learning is an end to itself.

The interesting thing about highly successful people is that most of them don’t stop working once they’ve “made it”. They continue climbing the learning curve long after the millions from big exits have been wired to their bank accounts. Why? After years in high rate-of-learning roles, they discover that learning was an end in itself.

Though it may seem like money is spilling all over the streets in Silicon Valley, don’t get distracted by shiny objects.

Play the long game. Put yourself in a position to maximize your rate-of-learning, even—and especially—if it makes you a little uncomfortable. The long game is hard, but rewarding, because you’ll know you had the strength to make the steeper climb.

https://medium.com/p/56dddc17fa42

// But it doesn’t have to be a startup. A couple of years working at a furious pace on multiple accounts at a world-class idea factory like Crispin, Porter + Bogusky will teach you equivalent multiplier skills. Different from what I learned at a mobile startup. But just as valid.

I’ve taken this approach to learning, building up my design experience stack from a broad base of multidisciplinary knowledge and mental models.

Somewhere along the way, you become comfortable with the uncomfortable. Ambiguity becomes a signal for opportunity. And it’s another level of fun to apply what I know to solve problems. //

“There’s no longer any real distinction between business strategy and the design of the user experience.

The last best experience that anyone has anywhere, becomes the minimum expectation for the experience they want everywhere.”

– Bridget van Kralingen, Senior Vice President of IBM Global Business Services. Source.

// It’s even reached IBM… The awareness has matured into desire for great design. But for many organizations, still feels like early adolescence. Passionate wants and needs remain weakly articulated. Have a look at the litany of poorly written role descriptions for senior design roles. Or speak with current leadership and quickly uncover the gaps. The next great challenge is gracefully and successfully integrating design leadership/thinking/culture/process into organizations where design was not a founding core domain discipline. We’re seeing, and feeling, this pain now.

The new reality, of course, is that consumers no longer look at branded distribution channels as preferred or automatic destinations.

Consumers go wherever they can find content that appeals to them, often without any real awareness of the distribution channel itself. There may come a day when consumers cannot even name the broadcast or cable television networks that produce the shows they love. Viewers already go straight to the end-content asset when they watch on-demand cable or use over-the-top tools like Apple TV, Roku or Netflix. By 2020, magazine devotees may ditch their subscriptions in favor of following their favorite (already freelance) writers on Twitter and consuming stories from specific journalists. They will no longer be yoked to larger media franchises that force them to pay for content they don’t value.

In other words, it’s not that consumers don’t have a desired destination — it’s just that the destination will no longer be the distribution channel itself.

Consumers will navigate straight to content, bypassing the former arbiters of what was good or bad. And as consumer navigation evolves, marketers and agencies will increasingly surface new mechanisms for content discovery and advertising alignment:

– The ease of being found within an interface (such as cable VOD or other over-the-top technologies like Roku) or search setting

– The ability to cultivate attention within personal networks via word-of-mouth or social media (Facebook, Twitter, Digg, etc.)

– The unpredictable moment of breakthrough, when the wisdom of crowds dictates a trend and allows a specific content asset to bask in a moment of glory and adulation

These new discovery mechanisms represent a dramatic but exciting change for advertisers that valued reaching the masses through high value placements like Yahoo’s home page or massive promotional efforts, such as blow-in cards falling out of your favorite magazines.

This new world begs for advertisers to create their own organic followership and cultivate audiences through social media and the continued smart use of search; it requires brands to thoughtfully present valuable experiences to end users that will thrive in the navigational structure of new platforms.

@borismsilver Yep. Solving problems is overrated. Meeting needs is better. Creating new needs is better yet.

— Marc Andreessen (@pmarca)

Make a radical change in your lifestyle and begin to boldly do things which you may previously never have thought of doing, or been too hesitant to attempt.

So many people live within unhappy circumstances and yet will not take the initiative to change their situation because they are conditioned to a life of security, conformity, and conservation, all of which may appear to give one peace of mind, but in reality nothing is more damaging to the adventurous spirit within a man than a secure future.

The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure. The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun.

If you want to get more out of life, you must lose your inclination for monotonous security and adopt a helter-skelter style of life that will at first appear to you to be crazy. But once you become accustomed to such a life you will see its full meaning and its incredible beauty.

Jon Krakauer (via observando)

Yep.