Some of the best life advice I ever got was this: Whenever you make a decision out of fear, you will regret it.I’ve applied that to writing, to relationships (and the end of relationships), to life.

I’ve learned to separate my fears from my intuition and, at times, to follow my intuition through the fear.

I’ve learned that love is a powerful antidote and can scare the demons back into the dark —

– but according to Pillay, the main enemy of fear isn’t love.

It’s hope.

When we send the action centers of our brain hope-based messages, they direct our attention and set our focus in very different ways than when we’re operating from fear-based messages.

As Pillay puts it, it’s like switching off the light that shines on the fallen tree trunk blocking our path, and switching on a light that shows the way around it.

Hope is much more than wishful thinking.

Hope is a way of moving through the world.

Pillay describes it as an hypothesis about the potential of the human unconscious. Hope quickens our imagination and prompts us to ask the right questions, acknowledging the challenges we face while searching out surprising answers, creative solutions, unexpected pathways that lurk beneath the fallen leaves.

It’s why successful people tend to be optimistic people. They rely less on existing facts to get what they want – or justify why they can’t get what they want – and use the blade of hope to carve out new facts, the kind that allow them to reach their goals.

When you send your brain the message Yes, this is possible, it will go to work sketching out what Pillay calls “motor maps” to lead you through the gap between where you are and where you want to be.

Keep in mind that none of this is likely to be easy. Then again, if it wasn’t difficult, or immensely difficult, you wouldn’t need hope in the first place.

Hope is necessary for action.

3

A man at my gym was diagnosed with terminal cancer.

The doctors gave him about three months to live. Six on the outside.

Chemo isn’t worth it, they told him. Think about your quality of life.

The man had a young daughter, and out of his love for her he decided not to go gently into the night: but raging, raging all the way.

He underwent chemo and revamped his diet. He showed up at the gym as often as he could. He lost his hair. He became scary-thin. Three months passed. Six. One year. More. His hair grew back. He regained the weight. Another year passed. More. The doctors were amazed.

Then the ground opened up: the tumors came back, a staph infection felled him, and the disease raced too far ahead for him to catch it again.

He died – more than three years after his initial diagnosis.

But he got those three years. Time to spend with his daughter. Time for his daughter to grow to know him, to more deeply remember him when he was gone.

News of his death saddened me, but also filled me with a kind of awe. That’s how you fight, I remember thinking. Even when you know you will lose in the end. (We all lose in the end. Death comes for us all.) You fight out of love, out of hope, out of everything you have. You fight out of the knowledge that every day — every single day of your life — is worth the battle.

4

But sometimes we’re afraid to fight, we keep our hopes small, so we won’t have to. We fear risk and disappointment and loss. Instead of using hope to counter the fear, we allow the fear to get ahead of us and shape our beliefs, our thoughts, our actions, our lives. And then we wonder why we stay stuck. Why we can’t seem to play a bigger game.

You can reset your life if you reset your attention. Thinking of the big picture can freak out your amygdala, which sees and registers it as threat. But, Pillay points out, you can think your way around this kind of fear by thinking small.

When you shift your mental energy from the big picture to the details of that picture, you shift to a different part of your brain.

The amygdala calms the hell down. You can breathe and think and act again.

So Pillay recommends that you write out a list of ten actions you need to take in order to achieve your big goal. Then you take one of those actions and break it down into ten smaller actions. Then you take one of those actions and…

You see where I’m going with this.

That way, you can dare to dream big while chunking the fear into smaller and smaller pieces until it disappears…for a while.

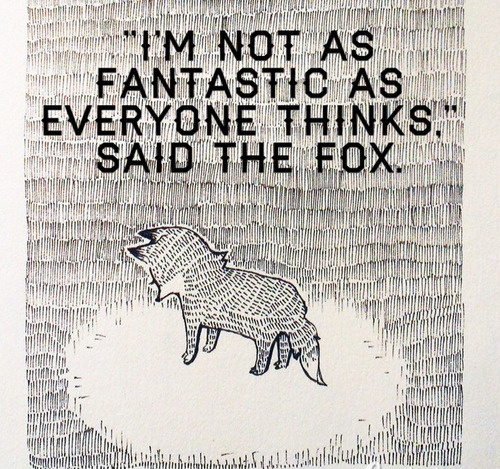

I don’t think that, as humans, we’re meant to overcome fear – unless you’re a sociopath who doesn’t feel anything at all (in which case you might have other problems, like how to avoid getting caught). We’re meant to lean into it, to learn from it.

You can use it to anticipate problems and then work to prevent those problems: to be productively paranoid. You can use it as an inner signpost, pointing to what you want to have, do and accomplish in your one wild and precious life. You can take it as a signal that you’re at your ragged edge, the outpost of your comfort zone, growing up and out into some better badass version of yourself: a version that lives in your mind’s eye, and you can slowly hope into existence.

5

So in one corner: fear.

In the other corner: hope.

Your brain is the arena.

You are the judge who declares the final winner.

Fear is a powerful beast. But we can learn to ride it. When we dare to hope for a certain outcome, and take action after action toward that outcome, we’re dealing with nothing less than the spirit of creativity itself.

And that, I realize now, was truly at the bottom of Pandora’s box:

The power of creation.

// http://bit.ly/fear_VS_hope